사방이 높다란 고개

분지에 터 잡고 교인촌 형성...교당 중심으로 일부러 미로 내 풍수지리적으로 '봉황 혈' 자리

동·서·남·북재로 구성

거주, 강학, 수도 다용도 공간...별채를 경전 간행소로 사용 밤에 호롱불 차단한 채 베껴써

誠敬信을 삶의 신조로

교도들 십시일반 먹거리 부조...40여 가구 전 주민 나눠 먹어

일부 교도 가산 털어 교당 후원

마을지형 이야기

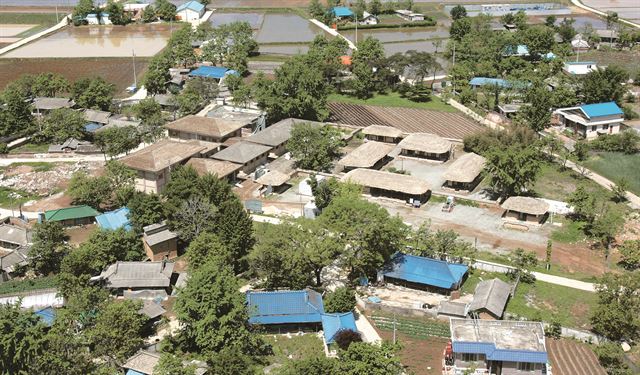

상주동학교당이 자리한 상주시 은척면 우기리. 1915년 김주희 주도로 교당 터를 다지면서 마을이 형성됐다. 우기리는 교당을 중심으로 미로(迷路)처럼 조성됐다. 교당으로 들어가는 길은 사방 10곳인데, 원래는 지게 멘 사람 하나 겨우 지나다닐 정도의 고샅길이었다. 이 길들이 얽히고설켜 거미집처럼 형성됐다. 교당에서 나고 자란 김정선(65ㆍ김주희의 손자)씨는 부친 생전에 “일제 때 순사들이 우리 마을에 한번 들어와 나가려면 똑같은 집을 기본 3번씩은 들락날락했다”고 했다.

교당은 산 아래에서 보면 칠봉산을 등에 업고 섰다. 우측에선 황령천이, 좌측에선 시암천이 감싸듯 흐르고 있다. 산 위에서 보면 고개로 빙 둘러싸인 분지에 있다. 동쪽으로는 한티재, 서쪽으로는 황령재, 남쪽으로는 서망재, 북쪽으로는 바구지재가 각각 있다. 김씨는 “사방의 재를 넘지 않고서는 10리(4㎞)를 못 간다”며 “교당의 지형적 위치가 일제의 감시를 피하는 데 큰 도움이 됐을 것”이라고 말했다.

우기리 초기 주민들은 주로 김주희를 따라 이주해 온 충청도 교도들이었다. 1918년 교당이 완공된 뒤 우기리(于基里)는 ‘우복동(牛腹洞)’이라고 불렸다. 김씨는 “풍수지리적으로 교당 터가 소의 배에 해당한다”며 “실제 마을 부근에 소꼬리에 해당하는 우재(牛峙)라는 고개가 있다”고 말했다. 우기리는 또 ‘창마을’ 혹은 ‘창리(倉里)’라고도 불렸다. 신라시대 때부터 왕실의 재물을 보관하던 창고가 있어서다. 1930년대 들어서는 부주교 김낙세의 인연으로 안동에서 넘어온 사람이 많아 ‘안동촌’으로도 불렸다.

3가지 이명(異名)이 지금까지도 회자되는 우기리는 배산임수, 분지, 미로로 상징되는 마을이다. 이를 토대로 종합하면, 교당은 지금으로부터 100년 전 동양사상에 입각한 길지에 방어ㆍ안락경(安樂境)까지 고려해 지은 특수공간이다. 무엇보다 일제의 감시망을 피해 한민족 고유정신을 전파하려 했던 김주희는 요새(要塞)를 꾀했는지 모른다. 이런 교당은 고지도로 보면 첩첩산중으로 둘러싸여 마치 ‘호랑이 눈’처럼 보인다. 김씨는 “할아버지는 아래서 보면 순탄한 평지지만, 칠봉산에 올라 보면 호랑이 눈을 연상케 하는 이곳에 교당을 짓고, 안으로는 우리 민족에게 동학사상을 전하고 밖으로는 일제와 동학정신으로 정면승부를 걸었다”고 이해하고 있었다.

교당배치 이야기

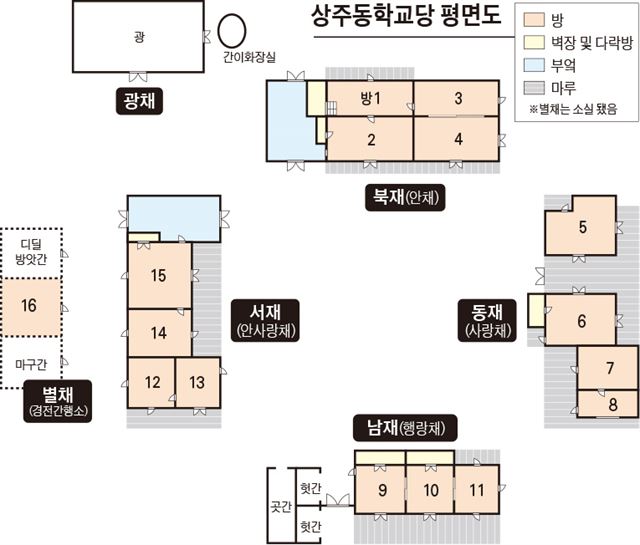

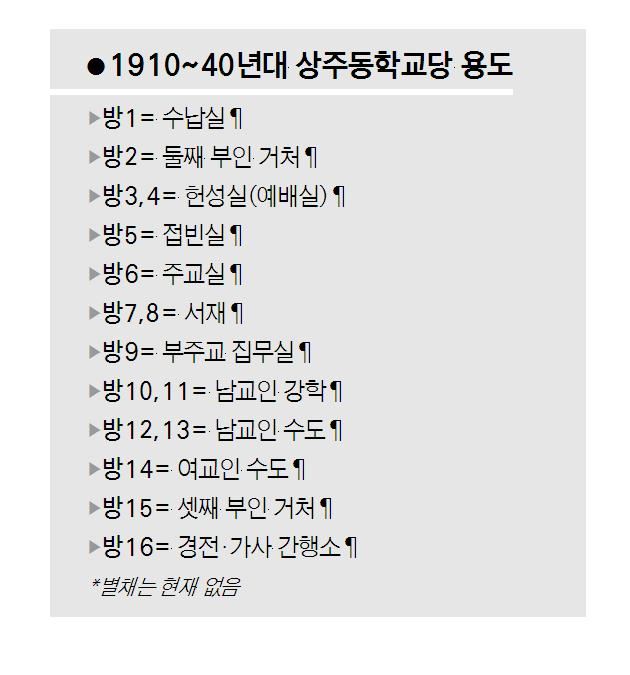

교당은 동남향으로 배치됐다. 건물은 모두 6채로 전통적인 가옥 구분에 따르면 행랑채, 사랑채, 안사랑채, 안채, 별채 그리고 곳간으로 이뤄졌다. 동학교도들은 이를 남재, 동재, 서재, 북재, 간행소, 곳간으로 각각 불렀다. 동서남북을 기본으로 동ㆍ서ㆍ남ㆍ북재를 앉혔고, 서재 뒤편 별채를 경전ㆍ가사 간행소로 사용했다.

1922년 일제가 상주동학을 공인했을 때도 경전ㆍ가사 간행사업은 자유롭지 못했다. 1936년 해산 통보를 받고는 일제의 눈을 피해 밤에 몰래 모여 별채 가운데 방에 거적을 걸쳐 빛을 가린 채 숨죽여 작업했다고 한다. 김 씨는 “생각해 보면, 당시 교인들은 정말 대단한 정신력을 갖고 있었다”며 “60촉짜리 전구도 없던 시절 잔솔가지로 호롱불을 밝혀놓고 경전이며 가사를 밤새워가며 옮겨 적었다”고 말했다.

안타깝게도 이 역사적인 장소는 1980년대 후반 허물어졌다. 해방 이후 교당이 와해되다시피 하고, 그 용도가 무용해지자 별채는 외양간으로 사용되다 산업화를 거치면서 애물단지로 전락했기 때문이다. 현재 교당은 동ㆍ서ㆍ남ㆍ북재와 곳간 그리고 헌성재로 구성돼 있다. 불교의 법당, 기독교의 예배당 같은 헌성실을 곳간 뒤편으로 이전한 결과다.

그 옛날 동재는 주로 교주 김주희가 사용했고, 서재는 김주희의 셋째 부인 하회 류씨와 여자 교도들이, 남재는 부주교 김낙세와 남자 교도들이, 북재는 둘째 부인 의령 남씨와 며느리 곽아기(89)씨가 각각 사용했다. 북재 맨 왼쪽 방은 쌍미닫이문을 경계로 앞 뒷방 모두 제(祭)를 올리던 헌성실로 사용했다. 교당의 특이한 점은 내부에 화장실이 없었다는 점이다. 이유는 명확하지 않다. 다만 1944년 병보석으로 풀려난 김주희가 거동이 불편해지자, 거처를 동재에서 둘째 부인이 기거하던 북재로 옮겨간 뒤 곳간 뒤편에 간이화장실을 만들어 썼다. 원래 화장실은 교당 정문 밖 골목 건너편에 있었다고 한다.

이런 교당은 동학사상의 결정체다. 상주동학은 인내천(人乃天), 인본(人本) 사상을 기본으로 풍수지리, 음양오행, 삼재(三才), 유불선(儒彿仙), 체천(體天) 사상을 융합했다. 교당을 풍수지리적 관점으로 보면, ‘봉황의 혈(穴)’ 자리에 해당한다. 칠봉산의 소나무는 봉황의 벼슬을, 교당 건물전체는 봉황의 몸통을, 조경수인 벽오동과 회화나무는 봉황의 먹이와 봉황의 꼬리를 각각 상징한다. 김씨는 “교당 오른쪽 유물전시관과 왼쪽 화장실은 봉황의 두 날개를 상징하는 것으로 전체적인 균형을 맞추기 위해 후에 지었다”고 말했다.

교당운영 이야기

교당에는 평소 교도 20~30명이 상주했었다. 이들은 교당에서 먹고 자며 더부살이를 한 게 아니라 우기리가 ‘교인촌’이었기에 수시로 오고가며 생활했다. 김주희를 중심으로 나름의 질서와 규칙을 가지고 공동체 생활을 영위해 갔다. 그들은 무명옷을 입고, 상투를 틀고, 농사를 지었다는 점에선 여느 농가와 별반 다를 게 없었다. 그들이 인근 마을주민들과 다른 점이 있다면, 그들의 정신이 동학사상으로 무장되었다는 것이다. 유달리 단합이 잘되었다. 김주희는 하늘에 정성을 다하고(誠), 어른을 공경하고(敬), 서로를 믿는(信) 불실기본(不失其本)을 강조했다.

삶이 넉넉하거나 풍족하지는 않았다. 저마다 못 먹고 못 살던 시절이었다. 그나마 큰 집회가 없을 때는 형편이 좀 나았다. 곽씨는 “철마다 교인들이 조금씩 양식을 가져와 못 사는 이웃들과 나눠먹었다”며 “문제는 큰 집회 때였는데, 팍팍한 살림을 아끼고 아껴 산다고 얼마나 힘들었는지 모른다”고 했다.

집회 때 많이 모이면 500명이 훌쩍 넘었다. 그러면 죽어나는 건 곽씨였다. 이유 불문하고 교도들 끼니를 책임져야 했다. 북재와 서재에 딸린 부엌은 곽씨의 전용공간이었다. 이곳에는 지금도 가마솥이 2개씩 놓여 있다. 평소에는 북재 부엌에서 끼니가 해결됐지만, 집회 때는 서재 부엌까지 풀가동해야 했다. 곽씨는 “말도 말아요. 내가 씻어낸 쌀뜨물만 해도 감바우못(인근 저수지)은 거뜬히 채울 것”이라며 “1년간 지내는 제 8번은 기본이고, 특별한 집회 때에는 쌀 1말을 안쳤다”고 했다.

교당은 한마을에 살던 교도들이 십시일반 보태기도 하고, 곽씨가 아끼고 아꼈지만 늘 적자에 허덕였다. 그때마다 가깝게는 문경, 예천, 안동 등지에 살던 교도들이 도와주고, 멀게는 강원도, 경기도 교도들도 품을 보탰다. 특히 상주 시내에서 한약방을 운영하던 박봉량(1879~1941)은 상주교당의 재정 후원자 중 한 명이었다. 그의 친인척 20여 가구는 우기리로 이주해 살았지만, 박봉량과 그 식솔들은 상주 시내에 살았다. 증손(曾孫) 박찬선(75)씨는 “증조부께서는 상주동학교의 재정을 돕고, 일제의 동향을 파악해 교주에게 전달하는 역할을 하셨던 것 같다”며 “상주 장이 열리는 닷새마다 우기리로 들어갔다가 하룻밤 묵고 나오셨는데, 그때마다 옷소매에 검은 먹물이 잔뜩 묻어 그걸 빨아 지우느라 할머니가 생고생을 하셨다는 얘기를 자주 들었다”고 했다.

그러니까 16개 방에 교인 20~30명이 상주하고, 집회 때는 평균 300~400명이 모인 상주교당은 기본적으로 안살림을 책임졌던 곽씨가 근검절약하고, 교인들이 십시일반 작게 돕고, 돈 좀 벌었던 박봉량 같은 이가 크게 도와 운영해 갔던 것이다.

교인생활 이야기

상주동학교당은 복합공간이었다. 김주희 일가가 사는 거주공간이자, 경전을 공부하는 강학공간이었다. 또 개별적으로 수양하는 수도공간이었다.

동학은 기본적으로 남녀평등을 주장했지만, 여전히 유교사상의 지대한 영향 아래 있었다. 옛법에 따라 남교인과 여교인의 생활공간이 달랐다. 드나드는 문도 달랐다. 남교인들은 남재 정문으로 드나들었지만, 여교인들은 서재 뒤편 쪽문을 통해 출입했다. 또 남교인들은 남재 부주교 집무실 옆방 2개를 주로 사용했고, 여교인들은 서재 방 일부를 사용했다.

각 방은 사정과 편의에 따라 그 용도가 달라졌다. 경전ㆍ가사 간행소로 쓰였던 별채 방은 낮에는 교인들이 모여 짚신, 멍석, 망태기 같은 생활용품을 만들던 공동제작소로 사용했다. 그러다 으슥한 밤이 되면 문에다 거적을 걸어 비밀공간으로 사용했다.

남교인과 그 자녀들은 부주교 김낙세에게 동경대전과 용담유사를 비롯해 천자문, 소학, 사서삼경을 수학했다. 교주 김주희는 동재에 거처하며 외지에서 온 손님을 응접하고, 시시때때로 일제의 동향을 살폈다.

상주동학의 특기할 만한 사항은 동경대전과 용담유사 목판을 100년 동안 온전히 보존하고 있다는 것인데, 구전으로 전해 내려오던 교조 최제우의 가르침을 필사하는 데 한계를 느껴 자체적으로 책판을 제작했다. 책판으로 쓸 나무를 마련하고, 각자(刻字)용 한자와 한글을 한 자씩 만들고, 새길 종이를 생산하는 등 경전ㆍ가사 간행사업과 관련된 업무 일체를 자체적으로 해결했다. 이 중 암수로 된 각자용 한자ㆍ한글은 100년 세월이 무색하리만치 방금 만든 것 같게 훤칠하다. 일제의 감시가 심해 사용할 엄두를 내지 못했기 때문이다.

40여 가구가 옹기종기 모여 살았던 우기리는 1943년 11월 25일 일제의 기습으로 곡절을 겪는다. 곧 해방을 맞아 몰수당했던 물건을 되찾은 것은 천우신조였다. 전 국토가 짓이겨진 한국전쟁 때 일대에서 상주동학교당만큼은 무탈했다. 일제 때는 순사가 검문 온다는 소식이 전해지면 집집마다 장롱이며, 곡식 가마에 물건들을 꼭꼭 숨겨 지켜왔다. 그 지난(至難)한 세월의 정통을 어기차게 지나온 물건들 앞에 이제 우리는 ‘유물(遺物)’이란 두 글자 명패를 놓는다.

심지훈 한국콘텐츠연구원 총괄에디터

題字: 혜정 류영희

Sangju Donghak (3)

The Hall of Sangju Donghak-Seated in a labyrinth

#The Terrain of the Village

The village of Woogi-ri, Euncheok-Myeon, Sangju City was first established by Kim, Joo-hee and his followers when they decided to open a new school there in 1915. The village itself was built as a maze with the Main Hall in the center. At first there were ten entrances to the village, each of which was so narrow that a man with an A-frame (old Korean style wooden backpack built to carry things) on his back could barely pass through. Inside the village, the linking lanes formed a labyrinth of cobweb. Kim, Jeong-seon (65), the grandson of Kim, Joo-hee, said, “My father told me that in his lifetime the Japanese freely came to our village, but they had a hard time finding their way out. They had to stray about the village at least three times, beating down the same alleys, before they found a way out.”

Seen from the lower area of the terrain, the village sits with Mt. Chilbong behind it. To the right of the village flows the Hwangryong Stream, and to the left the Siam Brook meanders along. Seen from a higher terrain, the site sits in a basin surrounded by mountain passes; to the east the Hanti-jae, to the west Hwangryong-jae, to the south Seomang-jae and to the north, Baguji-jae (Jae means a mountain pass).

Kim, Jeong-seon again emphasized the remoteness of the village. “Nobody could go more than two miles in any direction from here without passing through one of those passages. We believe the location of our village helped slacken the tight rope of the Japanese lookout.”

Most of the first settlers were the Donghak followers from the Chungcheongdo area, who gathered around Kim, Joo-hee. Completing the first settlement in 1918, they called it Woogi-ri or Woobok-dong. The former means a ‘New Place,’ and the second, literally a ‘Lying Cow Village.’ This name was inspired by the shape of a part of the terrain, or the Woo-jae Pass, which when seen from above looks like a cow tail, showing the village itself to be a cow lying on its belly.

The village, alias Woogi-ri, was once called “Chang-ri” or “Chang Maeul” from the Era of the Silla Kingdom (57 BC-935 AD). “Chang” means a storehouse. The ancient Kings cached their valuables in a warehouse in this deep, remote valley. In the 1930’s, led by the Deputy Leader Kim, Nak-sae, a group of Donghak followers came from the Andong area to live in the settlement. With the arrival of the group, the village was also called ‘Andong Maeul,’ after the new residents’ origin.

The village, which is still referred to as the three different names, Wooji-ri, Woobok-ri, Andong Maeul, is unique with its characteristics of the round valley, the maze of alleys and the good Feng Shui of ‘water in the front, mountains in the back.’ All these elements combined, the School Hall was intentionally built one hundred years ago as a special space befitting to the conditions of safe land and auspicious direction recommended by the Oriental Philosophy.

It seems that the Leader Kim, Joo-hee selected this site as the ideal bastion where he and his followers could study and spread the Truth of Donghak, with no disturbance in any form from the outside. In an old map, the Hall of Sangju Donghak looks like the eye of a tiger (see the photo).

Kim, Jeong-seon, the grandson of the first Leader, explained his understanding of the work of his grandfather. “My grandfather built the Hall and the village in this secluded valley which is shaped like a tiger’s eyes. He tried to enlighten the people with the teachings of Donghak and tenaciously made a frontal attack on the Japanese aggressors with the Donghak spirit.”

The Layout of the Hall

The Main Hall faces southeast, and the whole lot contains six traditional structures: servants’ quarters, guests’ quarters, inner quarters for guests, women’s quarters, an isolated quarters and a warehouse. The Donghak family call these structures the quarters of the East, the West, the South, and the North respectively, following the traditional order of the directions. They used the isolated quarters behind the West quarters as the rooms for copying or transcribing the Scriptures and Hymns.

Even when the Japanese Government-General officially approved Sangju Donghak in 1922, the transcribing of the Hymns and the Scriptures was not allowed. If they had been found violating the order, they were to be harshly punished. But the believers did it at night, under the dim lamp with thick straw mats covering the doors and windows.

Mr. Kim recalls, “Those people were so brave and faithful. With no electric light in the isolated hermitage, without using any copying tools, the pious followers devotedly hand-copied the Scriptures and the hymns secretly with writing brushes, letter by better.”

It is really a matter of regret that the old scripture copying building was demolished in the late 1980s. After the liberation of the country in 1945, the School itself lost its influence and was on the verge of closure. The structure had been used as a barn until it was removed.

The present Hall consists of six structures: the four quarters of the East, the West, the South and the North, as well as the warehouse. The last building located behind the warehouse is the Hunsung-sil Shrine, which is equivalent to the sanctum of the Buddhist temple or the Christian chapel.

At first, when they opened the village in the 1920s, the important members of the group lived in the quarters. The Leader Kim, Joo-hee used to stay in the East Quarters. Kim’s third wife Ryu from Hahoe and other women followers lived in the West Quarters. Deputy Leader Kim, Nak-sae and male believers stayed in the South Quarters. Leader Kim’s second wife Nam from Eui-ryong and Gawk, Ah-gi (now 89), the daughter-in-law, stayed in the North Quarters. The far-west room of the North Quarters with sliding doors between two compartments was used as the Hunsung-sil or the Shrine, where they held the ritual service. A strange thing about the layout of all the quarters is that there were no bathrooms in the buildings. No particular reason has been found for such a layout. In 1944, when the Leader was on sick bail from the police, he used a makeshift bathroom behind the warehouse near the North Quarters where his second wife lived. It is said that there used to be a latrine over the alley at a distance from the main gate.

The layout of the buildings in the Sangju Donghak compound symbolizes the harmonious aggregate of the Oriental Philosophy. In other words, it represents the crystals of Donghak, which balance essentials in the universe based on the following truths: (1) Humans are Heaven itself, (2) Heaven reveals itself through Humans, and (3) Humans are the center of all creatures. And the system of Donghak thoughts also embraces theories of Feng Shui, the harmony of Yin and Yang, three Wisdoms and the thoughts of Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism.

In view of the Feng Shui theories, the site of the Hall exactly overlaps the propitious spot of the Bonghwang, or the divine Phoenix. The pine trees on Mt. Chilbong denote the crest of the Phoenix. The entirety of the buildings of the Hall corresponds to the body of the auspicious bird, the Phoenix tree. And the pagoda tree planted in the garden are respectively equivalent to the feed (the fruit of the tree) and its tail.

Kim further explained that the two newly built structures, the Display Pavilion for the Remains on the right side and the restroom structure on the left, are the wings of the sacred bird. They were added to redress the balance of the whole arrangement.

#The Management of the School

There used to be twenty to thirty followers staying at the Hall, including the guests from the School branches in other areas. The residents there were the same in appearance as those living in the neighboring villages. They wore white clothes and had top hair topknots. They grew crops on their farms year round. But inwardly they were different; they were strongly armed with the teachings of Donghak. The Leader Kim, Joo-hee emphasized that the followers should practice the four principles of life; Seong (誠) (Devote Oneself to Heaven), Gyeong (敬) (Respect the Old), Shin (信) (Trust Your Neighbors), and Bul-sil-gi-bon (不失基本) (Stick to the Basics).

The finance of the School was not in easy circumstances, but rather was constantly in a state of pecuniary embarrassment. The Japanese police kept an eye on the village and questioned people entering with loads of crops. They often took away the bags of rice, saying it was not good to feed the betrayers.

The country was suffering financial failure at that time, and this was especially so at the School village. The villagers had to do anything they could to make a bare living through the year. The villagers used to share with each other whatever amount of rice or barley they had. But the hardest time for them was when a large number of visitors gathered at the Hall to pay homage to the deceased Founder on the anniversary of his death. In addition, the School’s regular meetings were held several times a year.

Gwak, Ah-ji (89), who was in charge of preparing and serving food, looks back on those unspeakable occasions. An average of 500 people would come from far and near and stay there for a couple of days. Some of them brought food for themselves, but the lack of food couldn’t be avoided.

Mrs. Gwak, the daughter-in-law of the Founder, was in charge of preparing the meals for all the guests. The kitchens belonging to the North and West Quarters were her working places. There still are two big cauldrons in each kitchen. Mrs. Gwak said, “Thinking of it, I don’t know how I did all the work. The water with which we washed the rice could fill the Gambawoo Reservoir down the hill. We had to prepare all the special servings eight times a year, and, especially on the anniversaries of the Founder’s birth and death, we steamed a full bushel of rice.”

The School’s operational expenses were chiefly appropriated by allotments from the villagers and some aid from the followers in other areas. Mrs. Gwak in charge of the financial management tried to economize on all expenses, but she had a lot of difficulty making ends meet. At some critical moments, the villagers practiced the saying, “Every little bit helps.” The followers living in other areas secretly participated in a fund raising drive. The contributions were made not only by the companions in the near areas of Moongyeong, Yecheon and Andong, but also by those in the relatively far provinces of Gyeong-gi and Gang-won.

Among those financial supporters, Park, Bong-ryang (1879-1941) is worth special mention. He practiced an Oriental Herbal Medicine clinic in Andong. His family of twenty members lived in this remote Woogi-ri where the School was located, while he was running the clinic in the County City.

Park, Chan-shin (75) talked about his great grandfather, Park, Bong-ryang. “My great grandfather seems to have helped Sangju Donghak both financially and by supplying them with information on the moves of the Japanese police. My grandmother told me the story she had heard from my great grandmother. The old man would visit Sangju on its market day and returned the next day with his white clothes stained with black ink. And my great grandmother did the washing with difficulty.” We can guess that he himself participated in the writing of the Scriptures and the lyrics under the pretext of visiting the market.

In conclusion, in all the sixteen rooms on the complex of the Hall, twenty to thirty residents lived with some migrating members. On the special occasions including the anniversaries, 400 to 500 people visited the School Hall. Mrs. Gwak, Ah-gi, then a young thrift-wise woman, was fully in charge of managing the livelihood and serving the visiting pilgrims. The voluntary donors including Park, Bong-ryang greatly helped the management of the School with some portions of the operational expenses.

#The Life of the Residents

The Sangju Donghak Hall was the center of multi-purpose buildings: a dwelling house for Kim, Joo-hee and his family, a printing house of the Scriptures, a studying and lecture hall for the members, and some others for the individual character building.

The equality of men and women was proclaimed as a creed, but the living custom itself was still under the strong influence of Confucianism; the living spaces of men and women were differentiated by their entrances. The men's residents used the gate of the Namjae, while the women were allowed an entrance and exit through a small gate behind Seojae. The men compatriots used two rooms next to the Deputy Leader’s Office in the South Quarters, whereas the sisters lived in the rooms in the West Quarters.

The use of the rooms was frequently changed according to the situations. For instance, the room at the Outhouse, which used to be the workshop for the straw bags or mats during the day, would become a secret room with the doors screened with thick straw mats.

The male compatriots and their children learned the Great Dong-gyeong Scriptures and the History of Yongdam, as well as Chinese Classics, from Kim, Nak-sae, the Deputy Leader. The Leader Kim, Joo-hee lived at the Dongjae where he used to meet the visitors who brought him information from the outside that helped him to lead the group wisely.

In the meantime, Sangju Donghak had been carrying out the most significant adventure. They set to manufacture the wood printing boards of the Scriptures, the History of Yongdam and other important creeds of Donghak. Most of them were the teachings of the Founder, which had been handed down orally. To this project, they gave their fullest commitment, selecting the best wood for the board, craving each letter in Chinese and Korean according to the use, and obtaining the paper for the books. They did all these things secretly for themselves, without any help from outside.

The letters, some in relief and some others in intaglio, are so clear and distinct even now that it is hard to believe that they were carved 100 years ago. One of the reasons that they have been kept so clean is that they hadn’t been used to make the books under the severe surveillance of the Japanese police.

In the village, some 40 households had lived peacefully until the 25th of November, 1943, when the Japanese attacked and wiped out the village and its residents. In the commotion, the Japanese confiscated all the materials concerning the Scriptures and other documents. Sangju Donghak followers believe that it was the will of Heaven for all the seized valuables to be returned intact to the School. Again during the Korean War that reduced the whole country to the ashes, Sangju Dong remained safe and whole.

Under the Japanese Rule, at a tip of Japanese overtaking, the compatriots deeply concealed what they thought to be the targets of the search operations. In front of the articles on display that have survived a series of ordeals, we only put a simple plate saying ‘Relics of the Past.’

Written by Sim, Ji-hoon, Editor in Chief of Hangook Contents Institute

The Inscription by Haejong Yoo, Young-hee.

Translated by Kim, Heedal & Hwang, Yongsoo (Ph.D) at LIKE TEST PREP (www.likestudy.co.kr)

기사 URL이 복사되었습니다.

댓글0